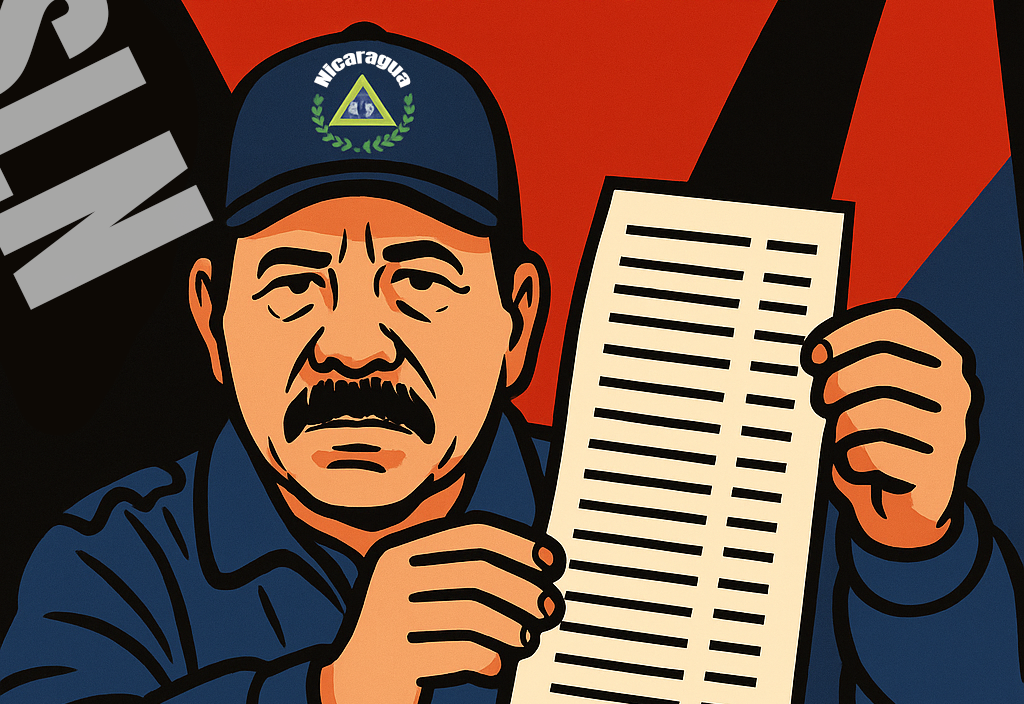

The Sandinista dictatorship led by Daniel Ortega and his wife Rosario Murillo has crossed a new threshold: on May 16, 2025, it enacted a constitutional reform that institutionalizes denationalization as state policy. Under the guise of “loyalty to the homeland,” the regime has codified collective punishment, erasing thousands of Nicaraguans from the legal, political, and economic fabric of the nation.

By amending Articles 23 and 25 of the Constitution, the regime has transformed denationalization into a systematic tool of political repression. No longer content with persecuting, imprisoning, or forcing dissenters into exile, it now strips them of their legal identity, rendering them stateless and severing all civil ties to their country.

Far from being a mere administrative measure, this reform constitutes a direct assault on the rule of law. It was imposed without public debate, without citizen consultation, and through a flawed procedure orchestrated by an illegitimate government operating under a distorted constitution. Moreover, it openly violates international treaties that guarantee the right to nationality and protection against statelessness, further underscoring its authoritarian and criminal nature.

From a legal standpoint, the reform violates fundamental principles such as due process, the right to defense, and the presumption of innocence. Affected individuals have no right to appeal or be heard, revealing the absence of legal safeguards in a country where the law has become an instrument of persecution. This measure revives and refines practices from the Sandinista era of the 1980s, when the revolution positioned itself as a source of law above any norm or treaty.

The reform includes a revealing exception: it allows dual nationality only for Central American citizens. Far from being a gesture of regional integration, this clause reflects the regime’s perverse logic—turning political asylum into a lucrative business. We have already witnessed how former Central American presidents accused of corruption have found in Nicaragua a comfortable refuge and a new political platform. The case of Mauricio Funes, former president of El Salvador, is emblematic: after being convicted of corruption, he was granted Nicaraguan citizenship and has continued his political life under the regime’s protection. Being a disgraced former Central American head of state now comes with a bonus—access to a new nationality and impunity.

The impact of this reform extends beyond the legal realm. Politically, it definitively closes the democratic space. Exiles who have acquired another nationality—whether in Spain, the United States, or elsewhere—not only lose their right to return but also their ability to vote, run for office, or participate in public life. The regime seeks to erase an entire generation of opposition, shielding itself from any prospect of alternation or return from exile.

An equally alarming economic dimension accompanies this reform. The state, cash strapped and cut off from some international financing, has found in this measure a way to legalize plunder. Thousands of properties, bank accounts, pensions, and assets belonging to denationalized individuals will be seized by the state without judicial order or compensation. The perpetual numbering system of the Property Registry will allow arbitrary confiscation and transfer of these assets, fueling a new “piñata” reminiscent of the mass confiscations of the 1980s—now with a veneer of legality.

The underlying motive is clear: the regime needs resources to sustain its repressive apparatus and has chosen to extract them from those it has already expelled. Retirees and contributors abroad may lose their pensions; economic migrants who maintained legal ties to Nicaragua will see all rights stripped away, including the right to legally exist as citizens. The strategy is perverse: to turn exiles into sources of remittances while denying them return and dispossessing them of everything they left behind.

In this context, it is no longer an exaggeration to ask whether Nicaragua is moving toward an extreme model of isolation, comparable to North Korea. The militarization of borders, internal segregation, and the progressive closure of the country are not distant scenarios but coherent steps within a strategy of absolute control, akin to those implemented in authoritarian regimes such as China.

In the face of this descent, the international community can no longer look the other way. It is urgent to activate mechanisms before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the UN Human Rights Committee—not only to denounce these crimes but also to protect those who have been stripped of their nationality, rights, and legal security. Likewise, it is essential that countries hosting Nicaraguans as migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, or under other forms of protection recognize the gravity of this regime-imposed “civil death” and respond with solidarity. Providing them with legal stability and humanitarian support would not only ease their uncertainty but also send a clear message against impunity and authoritarianism.

Ortega and Murillo are not governing—they are looting, punishing, and erasing. This reform does not merely revoke nationality; it severs the bond between thousands of people and their homeland, legalizes dispossession, and enshrines exile as state policy. It is definitive proof that Nicaragua is under a totalitarian regime that not only persecutes but also erases lives and legacies.

About the author:

Alex Aguirre | Nicaragua

Engineer, with studies in Law, Master’s in Conflict Resolution and Peace, and Director of the Institute for Peace and Development (IPADES)